This is the second deep dive into Power Testing ETL with Power BI. At this point, we have created the source table which will be used in our testing. The next step is to bring in the destination table and create the tests that will be “run” against the data. In its simplest form the tests are created using logical conditions based on whether source data matches destination data and calculations applied to those data sets also match. When they don’t match, you have data load error which results in a failed test.

This is the second deep dive into Power Testing ETL with Power BI. At this point, we have created the source table which will be used in our testing. The next step is to bring in the destination table and create the tests that will be “run” against the data. In its simplest form the tests are created using logical conditions based on whether source data matches destination data and calculations applied to those data sets also match. When they don’t match, you have data load error which results in a failed test.

How to Calculate Success and Failure

The basics of the testing is turn the results into numbers and calculate if and how much we succeeded or failed. Typically, every test will result in a 1 or 0. Whether you assign 1 to success or failure is largely dependent on how you plan to display your results. If you plan to use KPIs built into the Power Pivot model, you will be comparing the number of successful tests against the number of rows expected to be imported. The primary reason for this is that you cannot target zero when using KPIs. In this scenario, successful tests result in 1 and are therefore easily compared to the number of expected rows which would be 100% successful if they matched.

The other scenario is to measure failures. In this case, we assign 1 to each failed test and count the number of failed tests. This can easily be handled in visualizations such as conditional formatting where 0 can be displayed as green and the number of failures change the state from from green to yellow then red. This helps identify the most commonly failed tests.

The method you choose is up to you and how you prefer to see the results. We will cover using both variations in visualizations, but for sake of brevity here, we will measure success against our row count. Success = 1; Failure = 0.

Creating the Power Pivot Tests

In order to create the tests, you need to open the Power Pivot window and add the destination table to the model. In our case we have created a table in the HughesMediaLibrary database called books that is our target. Here is the syntax for the target table.

CREATE TABLE dbo.Books(

BookID int IDENTITY(1,1) NOT NULL

CONSTRAINT pk_Books PRIMARY KEY CLUSTERED,

BookName varchar(100) NOT NULL,

Publisher varchar(100) NULL,

Genre varchar(50) NULL,

CopyrightYear smallint NULL,

AuthorFName1 varchar(100) NULL,

AuthorLName1 varchar(100) NULL,

AuthorFName2 varchar(100) NULL,

AuthorLName2 varchar(100) NULL,

AuthorFName3 varchar(100) NULL,

AuthorLName3 varchar(100) NULL,

AuthorFName4 varchar(100) NULL,

AuthorLName4 varchar(100) NULL,

AuthorFName5 varchar(100) NULL,

AuthorLName5 varchar(100) NULL,

PageCount int NULL

)

While I realize this is not a good normalized table, it serves our purposes well to build out the tests. This table needs to be added to the Power Pivot model before we can do the next steps.

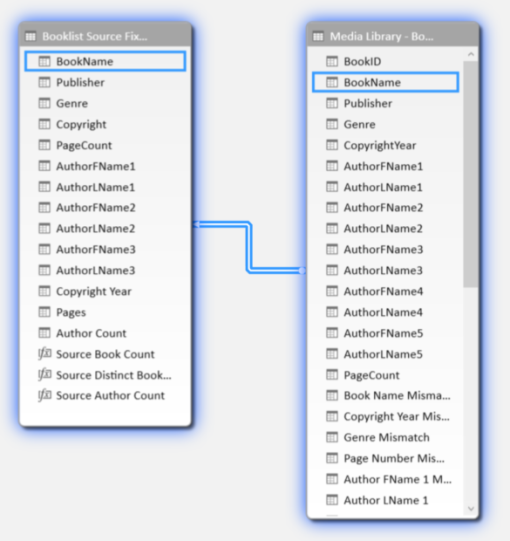

Relating the Source and Destination

The next step is to relate the source and destination. In our case, the only data that will work is the book name. We will use the Source table as the primary table in this relationship. The idea is that all the data in the source table should exist in the target. As this is not always the case, the source is the “source of truth” for the testing scenario.

Building the Tests

The tests are comprised of calculated columns that handle data analysis and calculated measures which summarize results.

Validating Data Field by Field, Row by Row

This is the primary reason that we worked with Power BI. One of the most common testing scenarios is whether the data came over correctly. In the previous post, we shaped the data with Power Query. Now we will compare it with the results from our ETL process in SSIS. We will use Book Name as the example. Every field you wish to test can follow this pattern. The test consists of a calculated column and a calculated measure.

We create a column in the destination table called Book Name Matches. (Remember we are tracking success not failures.) In each row of the data we need determine that the book name in the destination is the exact match for the book name in our source. We used the following DAX for that calculation:

=IF(RELATED(‘Booklist Source Fixes'[BookName])=’Media Library – Books'[BookName],1,0)

It looks at the related table to determine that the field names match. If they match, the test is assigned a 1 for that row. If they do not match, a 0 is assigned. (The table names are how I named the source and destination. They may not match your solution if you are following along.) Once we have the rows evaluated, we will sum the values with a Book Name Matches measure:

Book Name Matches (34):=SUM([Book Name Mismatch])

We will use the Book Name Matches (34) measure to compare with the book count. If they match, all tests passed. If they do not, then some or all rows have failed.

The number after the measure, 34, is the test key from TFS. I added this into the measure to make it easier to identify which test case is being evaluated with this measure. In some cases, you may have multiple measures that are required to complete a test. You can either evaluate them independently or create and additional measure that summarizes them for your use.

Other Validations or Tests

Some other basic validations can be created as well. A common one would the book count. In my scenario, I return the book count then evaluate it using a KPI. Another way to do this is to add another measure that checks for equality between the two book count measures in the source and destination. If they match, success. If not, failure.

You can also use measures to validate expected totals the same way we were working with counts. This is particularly helpful in financial data loads where you would want to verify a sum of balances to make sure the results match. The point is that you can add any other measures that you want to compare in order to meet the unique needs of your situation. It is also possible that you can compare to entered values. If you know that 100 widgets are to be imported, you can have the measure evaluate against 100 instead of a measure in the source.

Recording the Results in TFS

In order to bring the process full circle, we enter test results into TFS or Visual Studio Online. This allows us the ability to track test results, bugs, and fixes in a development lifecycle tool. It is also the best way to track testing history. One caveat here is that the query results from TFS do not permit you to set test results in Excel. Ideally, we should be able to link in the tests with the results. We could then update the results in the query and push it back. This is NOT supported at the moment. As a result, you will need to open the tests in TFS to update your results. This is not a significant issue because you should also create bugs for failed tests. It’s primarily a nuisance.

An added side effect of using this method to test is that we are able to collaborate with developers to determine what the bug actually is. Because all the data is loaded into Excel reviewing results is fairly simple and may actually be easier than trying to look at the destination system.

Quick Look at SSIS

Up to this point, we have focused on how an non-developer can set up the source and destination and proceed to test. I wanted to call out the author name work done in Power Query to highlight why Power BI is a great choice. When splitting author names, the work was done using right-click operations. Here is an example of the expression code used to split out the second author name column:

(DT_STR,200,1252)TRIM((FINDSTRING(AuthorNames,”,”,1) == 0 ? NULL(DT_WSTR,200) : TRIM(SUBSTRING(AuthorNames,FINDSTRING(AuthorNames,”,”,1) + 1,FINDSTRING(AuthorNames,”,”,2) == 0 ? LEN(AuthorNames) : 1 + LEN(AuthorNames) – FINDSTRING(AuthorNames,”,”,2)))))

Compared to Power Query, this is complex and not intuitive. While Power Query is not intended for enterprise ETL use, it’s simplicity helps test complex scenarios such as our author name split without having to create and equally complex SQL statement or expression.

The next post will take a look at some of the visualization options for the test results.