Within the Oracle Enterprise Manager suite of utilities, one that has been

around for some years is the tablespace manager that allows the DBA to

graphically see object distribution within the tablespace. After much searching,

I have found no equivalent utility on the SQL Server market, and some would

argue that there is no real need. Either way, this article provides the catalyst

for such a product and presents a text based solution you can explore this with.

What does the Oracle Tool look like?

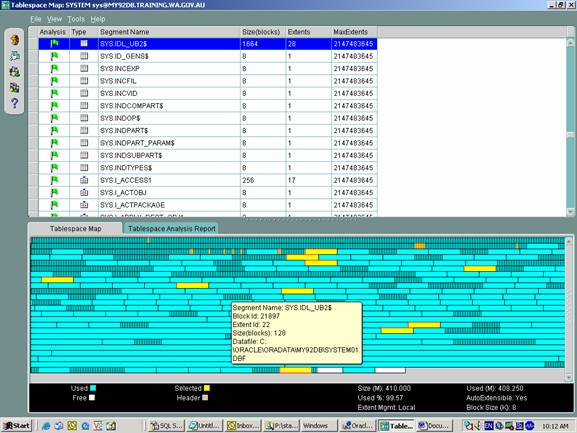

For those wondering what the Oracle GUI tool looks like, here is a screen shot

of my local database and the SYSTEM tablespace (filegroup in SQL Server):

Segments in Oracle are equivalent to SQL Server objects that take up physical

storage within a file-group. Note that segments have growth properties in the

form of extents (made up of 2 or more blocks or pages in SQL Server), and the

extents can be fixed or variable in size (multiple of the tablespace block

size). As such, the map shows for the selected object its space allocation,

with a bunch of small “patches” of allocated space then a seemingly even extent

growth later. This sort of dynamic allocation is a feature of Oracle and in

earlier versions of Oracle (not utilising local extent management features and

even/same extent sizes for all tablespace objects), was a bane for fragmentation

and free space management.

The DBA can switch between graphic and text views in this screen, and is

provided with analysis reports of segments fragmentation and row migration (not

applicable in SQL Server). From the Tools Menu we can perform a variety of

operations related to fragmentation with an approximation of the equivalent SQL

Server command:

Text based equivalent for SQL Server

To produce an equivalent result set in which a character or GUI based tool

could sit on top of, I utilised two core routines:

a) dbcc tab – list of data pages allocated for a table. Undocumented command

whose parameters from left to right are dbid, object-id, print-option

b) dbcc page – used to view page structure and associated data information.

Undocumented command whose parameters from left to right are dbid, pagenum,

print-option, cache, logical

The DBCC PAGE command returns the following information (parameter dependent of

course):

PAGE: (0:0)

-----------

BUFFER:

-------

BUF @0x18F81800

---------------

bpage = 0x19C10000 bhash = 0x00000000 bpageno = (1:70)

bdbid = 5 breferences = 1 bstat = 0x809

bspin = 0 bnext = 0x00000000

PAGE HEADER:

------------

Page @0x19C10000

----------------

m_pageId = (0:0) m_headerVersion = 0 m_type = 0

m_typeFlagBits = 0x0 m_level = 0 m_flagBits = 0x0

m_objId = 0 m_indexId = 0 m_prevPage = (0:0)

m_nextPage = (0:0) pminlen = 0 m_slotCnt = 0

m_freeCnt = 0 m_freeData = 0 m_reservedCnt = 0

m_lsn = (0:0:0) m_xactReserved = 0 m_xdesId = (0:0)

m_ghostRecCnt = 0 m_tornBits = 0

Allocation Status

-----------------

GAM (1:2) = ALLOCATED SGAM (1:3) = NOT ALLOCATED

PFS (1:1) = 0x0 0_PCT_FULL DIFF (1:6) = CHANGED

ML (1:7) = NOT MIN_LOGGED

DATA:

-----

Memory Dump @0x19C10000

-----------------------

19c10000: 00000000 00000000 00000000 00000000 ................

19c10010: 00000000 00000

<..etc..>

This command is relatively slow to execute in bulk, but provides in-depth

knowledge of the page, its allocation and associated linkages. This is a trade

off to the DBCC TAB command that, for each object within a database, will

provide a list of all pages related to the object albeit with minimal

information:

It is true that other system tables and combinations of other commands may

assist in generating similar output, all of which could speed the runtime

collection of data at a page level. Even so, I opted for the DBCC commands with

varying success. Due to the speed issues with DBCC PAGE and stripping data out

for the text returned, I coded two similar routines:

a) GetDBFileGroupMapping (dbcc page)

b) GetDBFileGroupMappingQuick (dbcc tab)

The logic for both is discussed next.

Supporting data collection table

Each of the routine below takes a “snapshot” of a database filegroups file

storage at a point in time. The routines utilise the same table (stored in the

master database) called for one of a better work “dbo.FGMapperPageAlloc”.

To make life easy, there are two “primary keys”

a) natural key – database ID, file ID, page ID, snapshot-date – cluster indexed

b) simple identity column (seq_no) – heap indexed

DBCC PAGE (GetDBFileGroupMapping)

The logic is simple enough. For the passed in database name, fileID and

optionally the max page number to scan too, we follow this logic:

- Validate database name and its file-id - don’t process log files

- Get total pages for the database file

- Ensure max page number parameter (if entered) is <= total size and >= 1

page

- Record current date/time as the snapshot date for this data collection

- For all pages in the file to validated maximum (when specified) do

- Run DBCC PAGE

- Parse out object ID and process

- Determine object type, properties

- Parse out current storage properties for the page

- Data, reserved counts, slot count

- Fill out denormalised information such as database-name, file-name,

file-group name - just in case things change at a later date and to save

further lookups later in reporting.

I would recommend that the routine be altered slightly to accommodate:

- null file-id (ie. process all non-log files for the database)

- rather than file-id, consider filegroup which includes all files for the

group

- include a row-count for the object at data collection time

- include the reserved count extract from dbcc page output

DBCC TAB (GetDBFileGroupMappingQuick)

The DBCC TAB command is wrappered into the “Quick” option. I found that DBCC

PAGE command too slow for large database files, the trace-on, dbcc page then

off, and subsequent parsing of long strings was taking close to a second per

page. For a large file the timeframe was ballooning out of proportion. The DBCC

TAB command was an effective “cop-out” that provided a relatively good

alternative.

The key logic is the call out to DBCC TAB as follows:

set @sqlstring = 'DBCC TAB (' + cast(@dbid as

varchar) + ',' + cast(@objid as varchar) + ',2)'

insert #DBCCTabOut

(PageFID, PagePID, IAMFID, IAMPID, ObjectID, IndexID, PageType, IndexLevel,

NextPageFID, NextPagePID, PrevPageFID, PrevPagePID)

execute(@sqlstring)

Note that a trace flag is not required to direct the output of the command.

The Mapper Routines (text based fragmentation report)

The final command is the display routine. The command was “hacked” together

to provide a text based “graphical” interface to view the dispersment of pages

in the database file. You basically tell the procedure the width of the screen

(multiples of 8 pages, or extents), the object(s) you want mapped, and it shows

the page distribution. The command is a little smarter though. If I pass in the

table name “mytable”, and it has three indexes, it will map these indexes as

well, each numbered differently and presented in a legend at the end of the map.

The examples provided later in this article give you can idea of the output.

GUI proposal for SQL Server

Here is a proposed mock-up screen for an equivalent tool for SQL Server 7 or

2000. The concepts are similar to that of the Oracle tool in terms of the grid

display that can be zoomed in/out and filtered down accordingly. The core areas

are:

1) DB Connections & Analysis selection

a. Tree like structure to navigate the collections made (server based)

b. Differentiates between full and quick scanned analysis

c. DBA can compare two analysis collections and toggle differences in the Grid

displayed

d. DBA can remove or archive collections

e. Collections can be “running”, ie. the collection process is multi-threaded

2) Object Filter and Results (for the selected collection)

a. Lists all table objects applicable to the collection

b. Lists all indexes associated with the selected table

c. The two options above dynamically change the display grid

d. Summary space usage information related to the object selected along with

current fragmentation data

3) DB and Filegroup summary

a. Instance version information (incorrectly called DB version in this

screen shot)

b. Total used space for data, index

c. Total number of table and index objects

4) Display Grid

a. Is GUI orientated

b. Can swap to a raw data view

c. Is clickable as per the Oracle equivalent

d. Grid pages will show popup information for more detailed data about the page

e. DBA can zoom in or out

f. DBA can view all objects (only free space is in white), and can click as need

be to highlight objects and the space they occupate.

i. Will also include slot counts per page (rows per page)

ii. Will include avg slots per page

Example Mappings

Before we begin, what are some raw facts about SQL Server 2k space

management:

a) Page – 8kb, smallest unit of IO, all pages consist of a header.

b) Extent – 8 contiguous pages = 64Kb

c) Segment – an oracle term, but relates to an object in SQL Server that is

allocated space in the form of pages (and subsequently extents).

d) Statistics (automatic or manual) – are binary blob rows identifiable in

sysobjects as _WA* and unless created by the DBA will be automatically generated

as table objects are queried via the auto-statistics database option.

e) Clustered Indexes – b*tree structure - leaf nodes represent the physical

table data, data is sorted by default in ascending order of the key.

f) Heap indexes – b*tree structure - consists of intermediary and leaf node

pages, leaf nodes have pointers to the physical data pages represented by a

bitmap lookup operation via the optimizer.

g) “Heap” table – a table with no clustered index, rarely used term – a heap is

a non clustered index and should remain that way.

h) Striping – space is allocated evenly over the two files based on their total

free space.

i) Mixed and full extent allocation – pages for a segment will be allocated in

mixed extents, that being an extent whose pages are owned by 2 or more segments.

If a segments space allocation exceeds eight pages, then SQL Server will

allocate space to this segment in blocks of full extents (reserved space).

j) Reclaiming space on deletion – removing rows and therefore logically freeing

space will not necessarily return this space back to the pool of unused pages

for any segment. The only way to guarantee this is via the truncate command.

Also note that index browning may occur with SQL Server as it does in Oracle,

in which removed rows space cannot be physically reused by the object (or

others) unless the segment has been defragmented. My testing with SS2k has shown

this is not a problem related to regaining free space. The use of a clustered

index and the online defragmentation command is an effective way to regain

space.

k) Slot counts – value represents rows per page

l) Fill-factor – reflected as a “percentage” controlling how much free space

will be reserved in index leaf nodes for future insertions/updates. This

directly affects the initial “packing” of rows/slots per page for clustered

indexes leaf nodes. Set to alleviate/control page splitting.

m) Pad index - will tell SQL Server to reserve space in the leaf nodes to cater

for subsequent updates. There is not numerical parameter for this option and

will be managed by the SQL Server engine.

n) DBCC INDEXDEFRAG - the table and indexes are available while the index is

being defragmented. The command has two phases:

a. Compact the pages and attempt to adjust the page density to the fillfactor

that was specified when the index was created. DBCC INDEXDEFRAG attempts to

raise the page-density level of pages to the original fillfactor. DBCC

INDEXDEFRAG does not, however, reduce page density levels on pages that

currently have a higher page density than the original fillfactor. (1)

b. Defragment the index by shuffling the pages so that the physical ordering

matches the logical ordering of the leaf nodes of the index. This is performed

as a series of small discrete transactions; therefore, the work done by DBCC

INDEXDEFRAG has a small impact to overall system performance. Figure 8 shows the

page movements performed during the defragmentation phase of DBCC INDEXDEFRAG.

(1)

o) DBCC DBREINDEX completely rebuilds the indexes, so it restores the page

density levels to the original fillfactor (default); or you can choose another

target value for the page density. Internally, running DBCC DBREINDEX is very

similar to using Transact-SQL statements to drop and re-create the indexes

manually. All work done by DBCC DBREINDEX occurs as a single, atomic

transaction. The new indexes must be completely built and in place before the

old index pages are released. (1).

So what does the file-group mapper show?, here are some interesting scenarios,

showing the movement of pages around the file-group from what we can gauge from

DBCC PAGE and DBCC TAB. Note that the mapper, at the character mapping level

only tells us what occupies a page, it doesn’t tell us if the space is used or

reserved. The underlying table used to support the map routine has more detailed

information of course related to the actual usage within the page.

Before I continue, please read the BOL for information related to the SGAM, GAM,

PFS and File Header pages.

Example 1 – DBCC PAGE Discrepancies and Space Reuse

The first example is an interesting one. I noticed the allocation of space to

a new user table resulted in the movement of two other system table objects.

Now, I am not trying to say that your database experiences the same results, or

that the tool is without error, but no matter when I run the DBCC PAGE routine

(and values for cache or logical options), the dump is reporting the movement.

The test is simple enough. We record the before and after images of the user

tables creation and the insertion of two 8k rows. Here is what I get:

Important – page numbering starts from page zero in all examples

Now if you thinking what I am, you’re probably wondering what the heck is going

on here. The two full extent allocations for mytest is unexpected and is not

reported by sp_spaceused. Even so, DBCC PAGE reports these pages are owned by

mytest. I may have expected a single page for the clustered index header, zero

leaf nodes, and two pages for the physical data; but why the additional 17

pages?

We also see systypes reduce by 1 page, and syscolumns reduce by 4 pages.

Here is the before image:

![]()

One item I haven’t mentioned here is the fact that I have been writing and

restoring back over the same database each time. Also note that I don’t normally

execute DBCC FREEPROCCACHE between mappings of the file.

Now here is the strange thing. The before image for page 337, 338 etc is telling

me that mytest exists? Funny that, because I haven’t created it yet! The

allocation as reported by DBCC TAB of course returns an error for mytest, but

these figures for systypes and syscolumns:

systypes, dbcc tab:

1 353

1 352

1 354

1 356

1 355

In the mapping via DBCC PAGE its reporting 36 and 37 as allocated. Again, no

matter the combination of parameters I use for this command, it still reports

its usage, unlike DBCC TAB.

syscolumns, dbcc tab:

1 26

1 45

1 60

1 74

1 85

1 88

1 91

1 299

1 30

1 16

1 17

1 18

1 319

1 29

1 320

1 321

1 322

Again, syscolumns is reporting 21 pages via DBCC PAGE and only 17 with DBCC TAB.

The after image reported this:

I was utterly confused with all of these figures. I ditched the database

instance completey and started fresh with a new instance and database files. The

next series of examples, with re-testing with DBCC TAB provides much more

comfortable figures. I simply wanted to stress the importance of testing and

re-testing with these commands.

Example 2 – Striping

The next example shows the objects space allocation amongst two data files

for a filegroup. The table has a single row of 8k with a clustered index. The

insertion of 50 rows and the creation of the files with default storage

properties give us this:

Legend

1 mytest (CLUSTERED/DATA)

2 mytest_ix (CLUSTERED)

U No object / unused

sp_spaceused 'mytest'

rows res

data index

unused

mytest 50

464 KB 400 KB 24 KB

40 KB

Example 3 – Mixed and Full Extent Allocation

The following series of tests attempts to map:

a) initial unallocated space as recorded by DBCC PAGE for a filegroup

b) how this space it utilised on creation of a new table with a custered index

c) follow the allocation of pages and extents for this object as we insert rows

d) see space allocation when another table of the same structure inserts data

concurrently with the original

e) the affect of dbreindex and indexdefrag commands on the filegroup and the

affect on the two tables

The database chosen is northwind, a single data file for the primary file-group.

The maps below are at a page level and divided into their logical extents. The

following shows used (zero) and unallocated (U) space, where DBCC PAGE has

reported no object owner within the page.

FileGroupMap

-----------------------------------------------

|FPGSUUUU|0U000000|000UUUUU|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00UUUUUU|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|0000UUUU|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|000UUUUU|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00UUUUUU|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000UUU|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|000UUUUU|000UUUUU|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00UUUUU

The following table is created, along with a clustered index and a single row

inserted.

create table mytest

(col1 integer identity(1,1),col2 varchar(8000))

create clustered index mytest_ix on mytest(col1)

insert into mytest (col2) values (replicate('-', 8000))

-----------------------------------------------

|FPGSUUUU|0U000000|000UUUUU|00000000|01110000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00UUUUUU|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|0000UUUU|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|000UUUUU|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00UUUUUU|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000UUU|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|000UUUUU|000UUUUU|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00UUUUU

A further 4 rows were inserted:

rows

resvd data

index unused

mytest 4

48 KB 32 KB 16 KB 0 KB

-----------------------------------------------

|FPGSUUUU|0U000000|000UUUUU|00000000|01111100|

|01000000|00000000|00000000|00UUUUUU|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|0000UUUU|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|000UUUUU|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00UUUUUU|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000UUU|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|000UUUUU|000UUUUU|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00UUUUU

Now a total of 11 rows, total space reported doesn’t seem to match 1:1 with page

allocation reported though via DBCC PAGE and DBCC TAB.

rows

resvd data

index unused

mytest 11 136 KB

88 KB 16 KB 32 KB

FileGroupMap

-----------------------------------------------

|FPGSUUUU|0U000000|000UUUUU|00000000|01111100|

|01100000|01100000|00000000|00UUUUUU|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|0000UUUU|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|000UUUUU|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00UUUUUU|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000UUU|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|000UUUUU|000UUUUU|11110000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00UUUUU

A larger number is inserted, checking the allocation of extents to the table. We

see contiguous allocation of space in extents, including the pre-allocation

(file extension) of extents at the end of the file.

rows resvd data

index unused

mytest 86

712 KB 688 KB 16 KB 8 KB

FileGroupMap

-----------------------------------------------

|FPGSUUUU|0U000000|000UUUUU|00000000|01111100|

|01100000|01100000|00000000|00UUUUUU|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|0000UUUU|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|000UUUUU|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00UUUUUU|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000UUU|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|000UUUUU|000UUUUU|11111111|11111111|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00UUUUUU|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|1111111U|

|UUUUUUUU|UUUUUUUU|UUUUUUUU|UUUUUUU

We finally increase this to 556 rows:

rows

resvd data

index unused

mytest 556 4488 KB

4456 KB 16 KB 16 KB

FileGroupMap

-----------------------------------------------

|FPGSUUUU|0U000000|000UUUUU|00000000|01111100|

|01100000|01100000|00000000|00UUUUUU|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|0000UUUU|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|000UUUUU|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00UUUUUU|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000UUU|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|000UUUUU|000UUUUU|11111111|11111111|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00UUUUUU|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|11UUUUUU|

|UUUUUUUU|UUUUUUUU|UUUUUUUU|UUUUUUUU|UUUUUUUU|

|UUUUUUUU|UUUUUUUU|UUUUUUU

I also ran DBCC TAB on 360 rows, double checking the DBCC PAGE command and its

results after the experiences I had with example one. The analysis seemed

accurate as shown below, and therefore I continued on with the DBCC PAGE

command.

FileGroupMap (DBCC TAB over mytest, 360 rows)

-----------------------------------------------------------------

|????????|0?000000|000?????|00000000|02211100|

|01100000|01100000|00000000|00??????|000??000|

|00000000|00?00000|00000??0|00000???|0000????|

|00000000|??000000|0????000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|000?????|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|000000??|00??????|??000000|0000??00|0000????|

|00000000|??000000|0000??00|00000???|??000000|

|0??00000|00000???|?0000000|00000???|?0000000|

|000?????|000?????|11111111|11111111|00000000|

|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|00000000|

|00000000|00??????|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|

|11111111|11111111|11111111|11111111|1

Legend Object Name

? Page not analysed

0 Allocated to another object

1 mytest (CLUSTERED/DATA)

2 mytest_ix (CLUSTERED)

Moving on with the 560 row example, we have these fragmentation figures.

DBCC SHOWCONTIG scanning 'mytest' table...

Table: 'mytest' (1621580815); index ID: 1, database ID: 6

TABLE level scan performed.

- Pages Scanned................................: 561

- Extents Scanned..............................: 73

- Extent Switches..............................: 72

- Avg. Pages per Extent........................: 7.7

- Scan Density [Best Count:Actual Count].......: 97.26% [71:73]

- Logical Scan Fragmentation ..................: 0.00%

- Extent Scan Fragmentation ...................: 2.74%

- Avg. Bytes Free per Page.....................: 77.0

- Avg. Page Density (full).....................: 99.05%

Deleting a range of data from the table, we so no difference in the map. By the

space usage routines and show contig results differ:

delete from mytest where id between 150 and 350

rows resvd

data index

unused

mytest 360

3080 KB 2904 KB 16 KB 160 KB

DBCC SHOWCONTIG scanning 'mytest' table...

Table: 'mytest' (1621580815); index ID: 1, database ID: 6

TABLE level scan performed.

- Pages Scanned................................: 360

- Extents Scanned..............................: 49

- Extent Switches..............................: 48

- Avg. Pages per Extent........................: 7.3

- Scan Density [Best Count:Actual Count].......: 91.84% [45:49]

- Logical Scan Fragmentation ..................: 0.00%

- Extent Scan Fragmentation ...................: 6.12%

- Avg. Bytes Free per Page.....................: 77.0

- Avg. Page Density (full).....................: 99.05%

DBCC execution completed. If DBCC printed error messages, contact your system

administrator.

Doing further deletions, again the figure changed as expected, but the map does

not, with DBCC PAGE returning the fact that the table still occupies the space

allocate to it when the 556 rows were inserted.

delete from mytest where col1 between 135 and 136

delete from mytest where col1 between 143 and 144

rows

resvd data

index unused

mytest 356 3016 KB

2864 KB 16 KB 136 KB

DBCC SHOWCONTIG scanning 'mytest' table...

Table: 'mytest' (1621580815); index ID: 1, database ID: 6

TABLE level scan performed.

- Pages Scanned................................: 356

- Extents Scanned..............................: 49

- Extent Switches..............................: 48

- Avg. Pages per Extent........................: 7.3

- Scan Density [Best Count:Actual Count].......: 91.84% [45:49]

- Logical Scan Fragmentation ..................: 0.00%

- Extent Scan Fragmentation ...................: 6.12%

- Avg. Bytes Free per Page.....................: 77.0

- Avg. Page Density (full).....................: 99.05%

DBCC execution completed. If DBCC printed error messages, contact your system

administrator.

Next, we run DBREINDEX, with UPDATEUSAGE after it, over the entire filegroup and

its tables/indexes, and also trial the defragmentation with INDEXDEFRAG:

Example 4 – Two concurrent table insertions

In this final example, we create the mytest table again, along with mytest2,

then run a concurrent insertion of 250 rows. Both tables include a clustered

primary key (identity). Here are the results:

Running the standard de-fragmenting routines we get this:

I repeated the example using DBCC TAB only, restoring back the database and

running the same scripts. Also note, I removed the 75% fillfactor value for DBCC

REINDEX.

Closing Comments

The scripts are far from complete and need some work from my initial

hackings; but do provide an interesting insight into the

allocation/de-allocation and movement of pages around a database files. This is

especially highlighted with the concurrent insertion example and would provide

some very interesting maps for the DBA to ponder on heavy OLTP database schemas.

The DBCC PAGE and DBCC TAB commands are strange beasts, and will require a lot

more in-depth analysis over my brief exploration to determine what is really

happening under the covers. From the basic set of examples, it is very

interesting to note the movement of pages via the defragmentation commands, and

more so, the allocation of more space to a filegroup in some cases. The movement

of pages and work performed will of course add to transaction log backup sizes

(where applicable) and possibly extended locking.

There is no doubt that IO fragmentation can degrade performance. The use of best

practice commands such as DBCC REINDEX, DBCC INDEXDEFRAG in your daily or weekly

maintenance plans is very important. Equally so, is having an understanding of

what these commands really do (especially the impact of shrinking filegroups),

and to some degree, the distribution of space within your busy client databases

for space planning and IO distribution monitoring.

I hope this paper provides the catalyst for more work in this area - along with

3rd party tools; and DBA’s marry the figures with other important areas, such as

effective buffer cache usage and IO statistics from ::fn_virtualfilestats().

Copyright © Chris Kempster, 2003

www.chriskempster.com

References

(1) Microsoft SQL Server 2000 Index Defragmentation Best Practices (2003),

http://www.microsoft.com/technet/treeview/default.asp?url=/technet/prodtechnol/sql/maintain/Optimize/SS2KIDBP.asp